Harry Chew, a painter and art professor at Cottey College and held Art therapy classes Nevada State Hospital #3

I remember one patient who would walk the front entryway grounds everyday, all day. We called him George. We would ride our bikes down and just sit and watch George walk around (I was in 3rd grade around 8)

The local little league baseball field was located just across the street from the hospital. In order to get to the ball park you had to pass the hospital. We then moved to N. Main Street and as a kid age (8-13) my brother Marty age (13-15) played on a ball team. Mom and Dad would be at work in the evenings and the only way Marty had to get to the park for his game and practices was on his bike. He would put me on the back and I would ride down the big hill from the Main street house with him. He did not want to leave his bike at the park so I rode it back up the hill! I was always a little "scared" passing the hospital by myself at dusk.

I always wondered about the people inside the hospital and of course their was always stories circulating. I know now that

During the 1800's - 1960's, thousands of people were committed and "housed" here. Many patients were used as test subjects for experiments that would aid in research for the future 'Medical Industry' and/or to control the 'moron' community, segregating them from Society to defer propagation. It was also very easy to commit relatives or spouses due to: 'Feeble-mindedness', 'Epilepsy', 'Menopause', 'Depression', 'Illegitimate Births' and 'Syphilis'. Mostly people in Nevada acted like it did not exist!

The doors of the Nevada Insane Asylum opened on July 1, 1882, servicing 148 Missouri residents, many who were transported by rail from Stockton, California due to overcrowding. The Missouri State Hospital #3, has undergone several name changes over the years including: 'The Lunatic Asylum Number 3', 'State Hospital for Insane, Number 3' and the 'State Asylum Number 3'. Eventually it was referred to by the more politically correct title as: 'State Hospital Number 3'. We just called it "The State Hospital " It was the largest employer in Nevada. The majority of the population worked at State Hospital.

Morrill J. Curtis supervised the building's construction and was appointed four years later to design Morrill Hall, named after Senator Justin S. Morrill. The original stone house was built during 1901-1904.

In the beginning the Nevada Asylum was intended as a working farm and functioned through the 1960's. Crops grown included alfalfa, fruit trees, vegetables, cattle, pigs, chickens and a dairy. Irrigation was provided from the Truckee River and domestic water was pumped to a water tower on the grounds, using the river's flow to power the electrical generator. Most of the farm products were used to feed the staff and 'patient's' of the facility and often, in times of abundance, leftover produce was sold at the town market. The grounds also included maintenance shops, a laundry, several barns, a boiler plant, morgue and cemetery.

The majority of the male population were farmers, laborers and miners while most of the female patients tended to come from 'housekeeping' occupations and were 'encouraged' to help out with the farm chores, without pay. New treatment methods for the 'insane' began to evolve towards a more 'humane' method believing that "fresh air and sunshine" would be beneficial for the 'poor unfortunates'.

Over the years, the Asylum Nevada Legislature failed to keep up the property and, along with overcrowding, conditions worsened. By 1895, the building contained 196 patients, 36 over the 'maximum limit'. Later that year, the State Legislature approved funding ($15,000), to build an annex onto the eastern end of the building, making room for an additional 75 patient's. During the late 1980's, State funding for these institutions had been significantly decreased and without further options for the out-dated facilities, many have been torn down. The buildings pictured were demolished in 1999.

One of the patients emerged as "An Outside Artist" with drawings discovered after his death. James Edward Deeds was placed in the hospital by his very strict father because he was "over active" child.

No one who knew James Edward Deeds when he was growing up on the family farm in Ozark, some fifteen miles south of Springfield on the banks of the Finley River, recalled him as an artist. When the boy, always known by his middle name, wasn't working in the fields, he preferred to spend his time hunting and fishing.

His father, Ed Deeds, was by all accounts a hard man. He served for ten years in the Navy as a paymaster, most of them in the Panama Canal Zone, where Edward, the eldest of five children, was born in 1908. Twenty-five years later, when he was admitted to the Missouri State School for the Feeble Minded, someone (likely his father, who signed the paperwork) reported that Edward's "peculiarity" first emerged soon after the family moved back to Missouri, when he was eleven. (Earlier this summer Julie Phillips obtained the admission form, along with the rest of what remained of her uncle's medical records, from the Missouri Department of Mental Health and shared them with Riverfront Times.)

The official diagnoses were "dementia praecox — paranoid type" (i.e., schizophrenia) and moderate mental retardation. (His nieces disagree: Williams, who has been a registered nurse for 42 years, believes he was autistic. Phillips, whose son has ADHD, thinks he was hyperactive.)

In 1941 electroconvulsive therapy, also known as ECT, was introduced at State Hospital No. 1 in Fulton. It's likely the new form of treatment came to Nevada at about the same time; by 1952, according to a report by chief of psychological services Dr. Gerald (Bud) Prideaux, it was "the most widely used form of treatment for mentally ill patients."

All patients, regardless of diagnosis, received ECT twice a week. One at a time, they were strapped to a table with electrodes attached to their heads, given a piece of rubber to bite down on and "jolted." The procedure typically left burns and bruises. There was no anesthesia. The idea was to temporarily erase patients' memories so they could go through what Prideaux called "emotional re-education" and eliminate "thoughts and actions which are abnormal and detrimental."

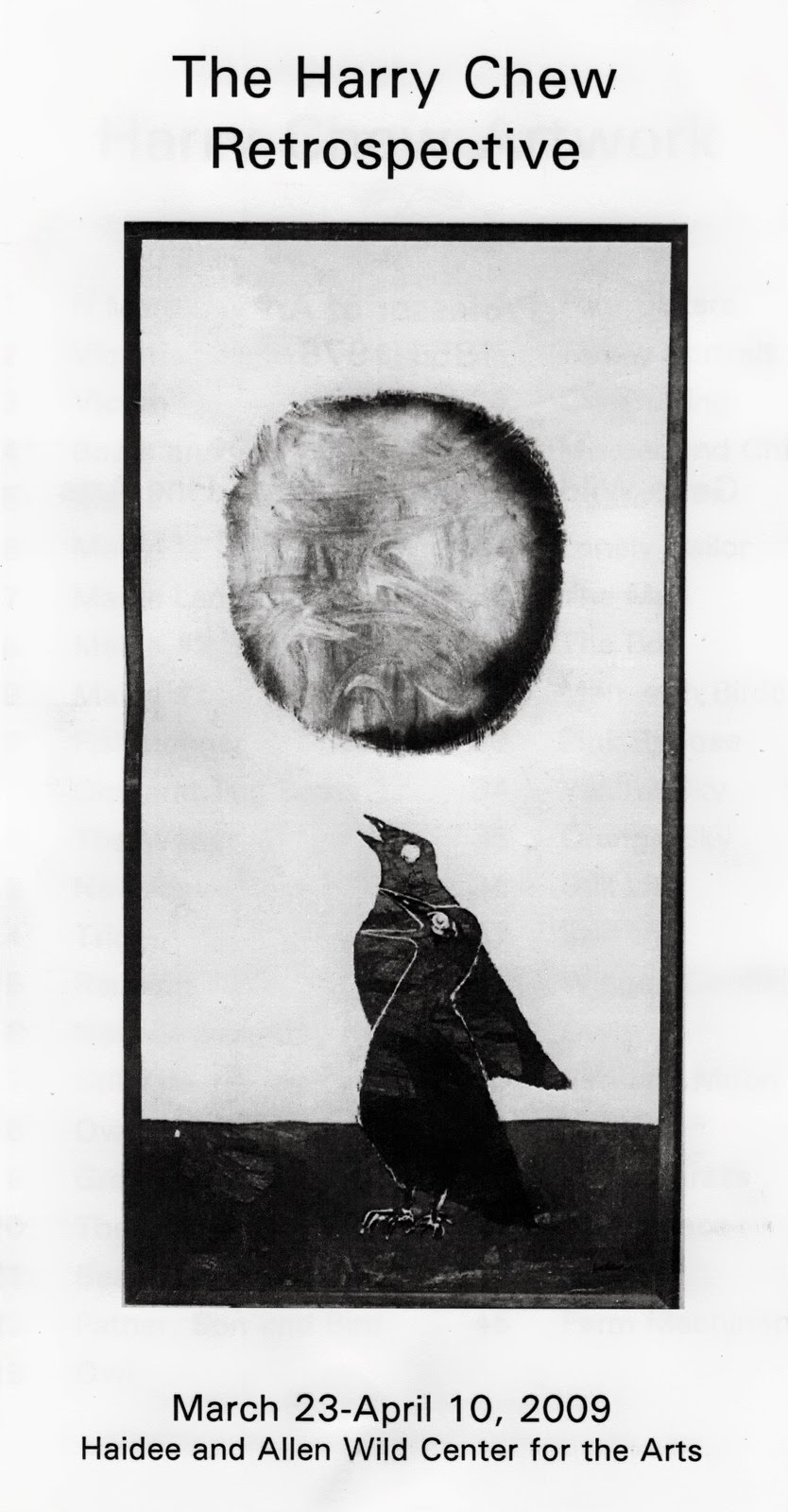

In 1953 Harry Chew, a painter and art professor at Cottey College in Nevada, began working with hospital patients two evenings a week, practicing an incipient form of art therapy. One of his students produced an oil painting of St. Dymphna, the patron saint of mental illness, that won a blue ribbon at the state fair and remains on display at Nevada's Bushwhacker Museum. But Chew's widow, Dodi, doesn't recall her husband ever mentioning Edward Deeds. "I don't think he took lessons," she says. "He just did his own thing." In my research I believe that Harry Chew did have an impact on him.

Deeds' mother bought him colored pencils at Kresge's five-and-dime, and someone at the hospital kept him supplied with tablets of outdated ledger paper. During family visits, while the adults talked and the children ran around and played on the grounds, he would sit with his pencils and paper and work with fierce concentration, ignoring all the noise and chatter around him. Little Tudie Williams liked to draw, too, and sometimes she would sit with him while he worked.

In the late 1950s, State Hospital No. 3 moved from electroshock toward sedation. A centennial report prepared in 1987 notes that Dr. Paul Barone, the institution's superintendent during the 1960s, "reports that with the help of tranquilizers many noisy, screaming, combative clients were changed almost overnight to quiet, orderly people."

Medical records show that Edward Deeds underwent his first drug treatments in 1968: chlorpromazine (Thorazine) for schizophrenia and benztropine mesylate (Cogentin), an antiparkinsonian medication, to control body tremors. The following year his doctor added imipramine (Tofranil) for depression. By 1972 Deeds' official diagnosis had been altered to "mentally retarded." A social worker notes in an official report from that year that "[h]e is undemanding and doesn't want people giving him too much attention. Usually sits quietly in a chair."

Having pronounced Deeds docile and no longer a danger to those around him, Barone recommended that he be discharged. His mother was too debilitated from arthritis to care for him, and his sisters were too busy with their farms. In an interview with the hospital social worker, Martaun Deeds explained that Clay was chronically ill (he had diabetes) and that between two working parents, three adolescents in the house and another daughter who'd returned home with her own two kids after a divorce, the household was too chaotic to take in her brother-in-law. She also felt it would be unsafe to leave Edward alone with the children.

Instead Deeds was transferred in January 1973 to the Christian County Rest Home, a nursing home in Ozark now called Ozark Riverview Manor. He lived there until 1987, when he died of a heart attack at age 79, having outlived four of his siblings (and both parents). His remains were interred in the family plot in Ozark Cemetery. State Hospital No. 3, later renamed the Nevada Habilitation Center, was torn down in 1999. At the time, Dodi Chew recalls, all the artworks that had been created by the patients and hung on the hospital's walls were destroyed.

The Electric Pencil: A long-lost cache of sketches by a state mental hospital inmate finally yields up some of its secrets

http://www.riverfronttimes.com/2012-09-14/news/electric-pencil-edward-deeds-outsider-art-mental-illness-harris-diamant-springfield-state-hospital-missouri-electroconvulsive-therapy/?ref=navigation

| ||||||||||||||

Comments

Post a Comment